Arm in Arm

Published on January 18th, 2018 by Diana Duren.

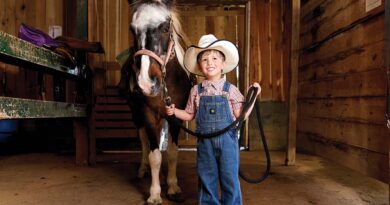

Two-year-old Delanie Neal tightly grips her baby doll in her dominant right hand, refusing to let go even when coaxed into using her left arm and hand to open a door or to eat. What are seemingly simple tasks to most can be more challenging for the toddler.

Two years ago, she had little, if any, movement in her left arm. It was paralyzed, kept tucked to her side and unused. She has made tremendous progress with occupational therapy and surgical intervention.

Delanie was born with Erb’s Palsy, a paralysis of the arm caused by an injury to the upper group of the arm’s main nerves, the brachial plexus. One to two babies in every 1,000 births have a brachial plexus injury, often a result of a very difficult birth delivery.

Her parents, Whitley Key and Adam Neal, from Clarkrange, Tennessee, learned 24 hours after delivery that Delanie had the brachial plexus injury. Key had a healthy pregnancy, but after being induced at 39 weeks gestation, she had a difficult labor and pushed for over two hours. Other than the difficult birth process, Delanie was born healthy, weighing 7 pounds, 14.5 ounces and was 19.9 inches long. The news came as a shock.

“I was overwhelmed and didn’t know what to think. You think nothing could go wrong and you wake up the next morning and they are telling you this is wrong with your baby,” said Key. “She had very limited motion of her arm. She could lift it up just a hair but it always stayed tucked up behind her. She would curve her wrist in, but it was kind of like the arm was dead. She didn’t even realize she had an arm.”

To help patients like Delanie, Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt has a Brachial Plexus Clinic, a collaborative effort among pediatric specialties — neurosurgery, plastic surgery and occupational therapy (OT) — to treat brachial plexus injuries from birth to age 18. In addition to birth-related injury, trauma can also cause injury to the brachial plexus. Treatment can range from intense occupational therapy to the need for microscopic nerve surgery, either by using nerve grafts to bridge across the damaged areas or by borrowing from another working nerve and using a portion of it to reinnervate the nonfunctional muscle.

Lindsey Ham, OTR/L, CHT, lead occupational therapist in the Brachial Plexus Clinic, works closely with families and helps coordinate access to OT services. Occupational therapy is a very important part of the recovery process. Ham evaluates and determines if patients are developing age-appropriate motor skills.

Recovery from brachial plexus injuries depends on the type and severity of the nerve injury. Damage to the affected arm may include loss of sensation, loss of control of the muscles that move the arm and hand, and/or loss of functional use of the arm or hand. Therapy includes caregiver education on range of motion exercises, positioning and functional activities to complete at home. Intense therapy is also needed intermittently to address specific functional goals.

Ham develops a close relationship with the families. She sees them once a month for the first year of life at a minimum. About 80 to 90 percent of pediatric patients with brachial plexus injury recover from their injury with intensive occupational therapy. But the other 10 to 20 percent will need surgery with hopes of regaining significant use of the paralyzed arm, though 100 percent recovery is unlikely.

“I love being able to be a part of this clinic and working with these children and their families. In my eight years working with this population, I have seen patients in all aspects of their childhood from infancy all the way to transitioning into college,” Ham said. “My goal is that they are able to accomplish any of their life goals. I have worked with children who were baseball players, football players, cheerleaders, golfers, wrestlers, gymnasts, hunters and involved in many other activities. They may have to perform the activities differently than others, but they can do it.”

If needed, surgery is typically performed between 6 months and 9 months of age. After age 1, the chance for recovery with surgery reduces significantly.

Key and Neal researched the brachial plexus in the days following Delanie’s birth and looked for care options through- out Tennessee, before deciding Vanderbilt — almost two hours from their home — would provide the best chance for their daughter’s recovery.

When Delanie was 2 months old, they met with Jay Wellons, MD, MSPH, chief of Pediatric Neurosurgery at Children’s Hospital. Delanie began occupational therapy in order to complete range of motion exercises for the arm to prevent contractures while waiting for the nerves to recover or “wake up.”

She did have some movement in her wrist and hand, but virtually no ability to bend the arm and no abduction (the movement of the arm away from the midline of the body).

“Not every child who has brachial plexus injury is going to have surgery, and in reality only about one or two out of 10 will need the surgery,” Wellons said. “It’s important not to have a surgical bias when making these decisions. That’s why it is critical to have Lindsey on our clinic team because she helps us make decisions. She can identify that certain patients are not getting any better (with OT) by the time interval we dis- cussed, and may be a candidate for surgery. She is a critical part of our clinic, our decision-making, and I am proud of the truly collaborative nature of it.”

Range of motion activities are critical in maintaining and preventing joint tightness or the development of contractures. Ham ensures that parents are instructed on how to perform range of motion exercises, typically performed at each diaper change. Safety precautions are also taught to avoid further injury to the affected arm such as not pulling on the arm or picking the child up under the arm. Instructions are also given on proper positioning to support the arm.

Ham teaches parents how to dress and play with their babies safely and without the fear of hurting them.

Key and Neal focused on OT sessions and exercises on their own time with hopes they could avoid surgery for Delanie.

“We had therapy two to three times a week, and some- times four. We were very dedicated parents and tried to do the best we could for her,” Key said.

When Delanie was 6 months old, she had made limited progress. She could barely lift her arm. After she received extensive OT for eight months, it was decided that surgery was the best option for recovery with the goal that she would hopefully achieve up to 80 percent functional use of her arm.

“It was heartbreaking that she would need surgery but to know they had confidence she would get some more movement back than she already had, we said we’re going to do this,” Key said.

Delanie had surgery in April 2016. Wellons worked in collaboration with Reuben Bueno Jr., MD, associate professor of Plastic Surgery, to perform several repairs in one sitting, combining procedures to loosen up the scar tissue around the brachial plexus, as well as using portions of healthy and functional nerves and “rerouting” them to healthy nerves and musculature by sewing the nerves together using suture around the size of a human hair. This technique is called neurotization, and Wellons has published extensively on this procedure in infants and children over the last 15 years.

“Delanie is doing great. She’s getting her hand to her mouth and getting her arm out,” Wellons said. “I really feel like it’s our public health responsibility to provide a place for children with brachial plexus to go for their care. We are well suited to be able to handle this complex care here at Children’s Hospital.”

Delanie continued with occupational therapy two to three times a week post-surgery.

“Any little thing she would do, we would always be excited if she lifted her arm up even a centimeter more or made a new movement. It was definitely a life-changing experience,” said Key.

“She does a lot on her own — way more than we could ever imagine. She’s definitely sassy, very independent.”

Jaxon Newman, 14 months old, was among the majority of patients with brachial plexus injury who didn’t need surgery, but instead follows an intensive occupational therapy routine — both in clinic and at home.

His mom, Jaimie Newman, a chief warrant officer 2 serving in the U.S. Army at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, labored for 61 hours, which included about three hours of pushing, before Jaxon was finally born. The traumatic labor took its toll on the 9-pound, 14-ounce boy. His arm had been stuck on Newman’s pelvic bone and the umbilical cord was wrapped around his neck, limiting his oxygen intake.

He was born with the brachial plexus injury, and his kidneys weren’t working properly. He was sent to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Children’s Hospital. He had two stays in the NICU for kidney problems. Jaxon is the first child for Jaimie and her husband, Sgt. 1st Class Marshall Newman, who also serves in the U.S. Army at Fort Campbell in the 52nd EOD Company for the U.S. Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal.

Jaxon’s right hand was closed into a fist, he had little to no strength in his arm and he couldn’t raise his arm.

“Even if we had a completely healthy baby, we would still be nervous (since we were first-time parents),” said Jaimie, who serves in Charlie Company, 1-101st Combat Aviation Brigade. “For the first month, we didn’t even put many clothes on him and turned up the heat. We were afraid we might cause more nerve damage and lessen his chance of healing. It was not anything we knew about.”

At about 2 months old, Jaxon went to the Brachial Plexus Clinic at Children’s Hospital, and he began working with Ham in occupational therapy. Ham coached Jaimie and Marshall on how to do his exercises at home.

“(Ham) let us know we weren’t going to hurt him. We realized it wouldn’t cause pain to move his arm,” said Jaimie.

When Jaxon was 8 months old, the team thought he might need surgery, but after another month he improved and surgery was not needed. He continues occupational therapy at home, and has seen Ham every other week for six months. In January, a soft cast will be put on Jaxon’s good left arm and hand to force him to rely on and strengthen his right arm and hand.

At a recent appointment, Jaxon used his right hand to drop balls in a bucket and turn the pages of a book, occasionally trying to sneak in the use of his healthy left hand. He would also try to eat fresh blueberries his mom brought, frustrated when he couldn’t get one in his mouth. At one point, reaching up for his mom to pick him up, Jaxon’s right arm went high above his head — a sign of progress and a welcome sight for Jaimie and Ham.

“We’ve seen dramatic changes over the last few months,” Jaimie said. “Luckily, he won’t need surgery. Vanderbilt has a great team, and I’m so thankful he has been able to receive such phenomenal care.”

– by Christina Echegaray